This week’s Dance First Member Insight is a tribute to Anna Halprin contributed by The Tamalpa Institute.

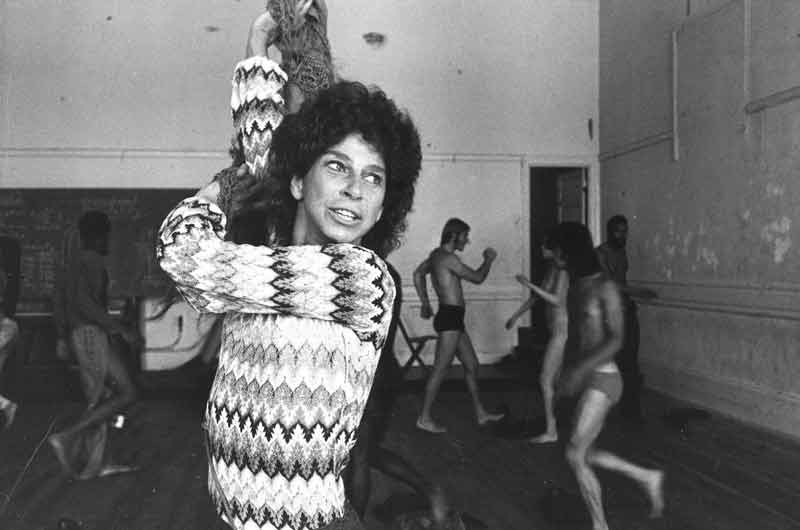

Anna Halprin, a dancer and choreographer who sought to move beyond what she saw as the constraints of modern dance and whose experiments inspired, challenged, and sometimes perplexed generations of dancers and audiences, died on Monday at her home in Kentfield, Calif., in Marin County. She was 100.

Fascinated by movement as a child, Ms. Halprin was encouraged by her parents, who enrolled her in dance classes and even occasionally had dance teachers live in their house. She attracted the attention of Doris Humphrey, one of the era’s leading choreographers, but Ms. Halprin knew that her family wanted her to attend college. She instead enrolled in the University of Wisconsin, Madison, which offered a progressive modern dance curriculum.

In a career that began in the late 1930s and took off after she moved to San Francisco in the mid-1940s, Ms. Halprin sometimes attracted controversy. But she also attracted students, disciples, and enthusiasts fascinated by the creative issues she explored and the way she explored them.

As a choreographer, Ms. Halprin stressed improvisation within structured limits. Her works included mysterious mood pieces like “Birds of America or Gardens Without Walls” (1960), in which stillness was as important as movement, and “Five Legged Stool” (1962), in which everyday actions were juxtaposed in unexpected ways.

She frequently looked for ways to involve the audience directly in her work and make social and political statements through dance. Ms. Halprin’s San Francisco Dancers’ Workshop made a spectacular New York debut at Hunter College in 1967 with “Parades and Changes,” a choreographic cavalcade of moods and situations with music by the electronic composer Morton Subotnick. In the work’s most unusual sequence, dancers slowly removed their clothing until they were totally nude, then just as slowly put their clothes back on, only to disrobe again and romp with long strips of crumpled-up paper, then roll into the orchestra pit.

There had been nude dance events in New York before, but never in so prominent a place. To forestall the possibility of police intervention, newspaper dance critics, who in those days often submitted their reviews immediately after a performance, agreed this time to wait until the weekend performances were over and the company had left town. (The Manhattan district attorney’s office filed indecent-exposure charges against the troupe a month later, although no further action was taken.)

Critics were generally impressed. Despite his reservations about the work as a whole, Clive Barnes of The New York Times called the nude scene “not only beautiful but somehow liberating as well.”

Her “West/East Stereo” (also known as “Animal Ritual”), presented at the 1971 American Dance Festival in New London, Conn., resembled a therapy session, with performers engaging in sometimes bellicose emotional encounters. The reaction was mixed. Frances Alenikoff praised the piece in Dance News as “a dive into the collective unconscious from which I for one emerged refreshed.” Doris Hering wrote in Dance magazine that “therapy is essentially personal” and not necessarily “much fun for an audience, especially when the performers are technically mediocre.”

Ms. Halprin went on to blur the distinction between performers and spectators by creating communal rituals in which everyone present participated; among them was “Circle the Earth,” which enlisted the audience as performers in what she called a “peace dance.” Drawing on her experience as a cancer survivor, she led movement workshops for people with cancer and AIDS.

In 1978, Ms. Halprin and her daughter Daria, who had been one of the stars of Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1970 film “Zabriskie Point,” founded the Tamalpa Institute in San Rafael, California. The Tamalpa Institute offers workshops in movement-based arts education and therapy.

In later years Ms. Halprin, who continued to dance until she was 95, returned to creating works for the stage, many of which addressed aging and death. “Intensive Care: Reflections on Death and Dying” (2000) confronted life-threatening illness.

Ms. Halprin’s husband died in 2009. In addition to her daughter Daria, she is survived by another daughter, Rana, and four grandchildren.

Just as her work often made little distinction between dancer and audience, Ms. Halprin made little distinction between dance and life. “Life experience is the fuel for my dancing,” she said in a speech at the University of California, Davis, in 2000, “and dance is the fuel for my life experience.”

We at Conscious Dancer would like to pass on our sincere condolences to the Halprin family and those who were touched by Anna Halprin and The Tamalpa Institute’s teachings.

PS: Our friend Jens Wazel was blessed with the opportunity to record video interviews and film Anna dancing five years ago in 2016. Please watch and share these rare moments.